Construction Library

Expand your knowledge in the construction industry.

227

Contributors

835

Articles

80

Topics

32

Tools

Featured Article

One way to improve your hit ratio is to focus on the right jobs for your business—which means skipping some bids entirely.

Read on for detailed information about each step of the construction bidding process.

Read MoreTechnology

Stay up to date on the latest technology trends and tools to build smarter, safer, and more efficient projects.

Explore TechnologyPro contributors

Explore more topics

Hands-on Procore education: learn tools and boost efficiency across all construction roles.

The Voices of Construction

Real stories, expert insights, and candid conversations from the people building our world.

The Voices of Construction

What’s Really Behind the Construction Productivity Gap?

With Peter Tateishi, CEO of AGC California, and Josh Bone, Executive Director of ELECTRI International

The Voices of Construction

Building Intelligence: How AI & Data Are Rewiring Construction for the Digital Age

With Scott Bornman and Marlissa Collier

The Voices of Construction

Can Modern Leadership Styles Accelerate the Construction Industry?

With Mel Renfrow, VP of Strategic Development and Marketing at Performance Contracting Inc. (PCI)

“You're no longer walking and crossing things off a list on paper. You're doing it on an iPad, and you have emails and correspondence documented.”

Danny Stumbras

Manager, Strategic Product Consultants, Specialty Contractors, Procore

The Voices of Construction

How Can We Bridge the Data Gap in Construction?

Eric Whobrey, ARCO Murray's VP of Innovation and Managing Partner explores the data gap and data maturity.

The Voices of Construction

How Can Technology Help Rebuild Construction’s Image?

With Todd Wynne, CIO of Rogers-O'Brien rethinking how we build, lead, and grow our future workforce.

The Voices of Construction

What’s Really Behind the Construction Productivity Gap?

With Peter Tateishi, CEO of AGC California, and Josh Bone, Executive Director of ELECTRI International

The Voices of Construction

Building Intelligence: How AI & Data Are Rewiring Construction for the Digital Age

With Scott Bornman and Marlissa Collier

The Voices of Construction

Can Modern Leadership Styles Accelerate the Construction Industry?

With Mel Renfrow, VP of Strategic Development and Marketing at Performance Contracting Inc. (PCI)

“You're no longer walking and crossing things off a list on paper. You're doing it on an iPad, and you have emails and correspondence documented.”

Danny Stumbras

Manager, Strategic Product Consultants, Specialty Contractors, Procore

The Voices of Construction

How Can We Bridge the Data Gap in Construction?

Eric Whobrey, ARCO Murray's VP of Innovation and Managing Partner explores the data gap and data maturity.

The Voices of Construction

How Can Technology Help Rebuild Construction’s Image?

With Todd Wynne, CIO of Rogers-O'Brien rethinking how we build, lead, and grow our future workforce.

All Resources

Featured Topics

123 Articles

101 Articles

95 Articles

42 Articles

107 Articles

43 Articles

159 Articles

47 Articles

145 Articles

Explore data and trends for building materials prices.

Get the latest U.S. retail prices and view historical trends for common building materials.

Page:

Free Tools

Calculators

Use our calculators to estimate the cost of construction materials for your next project.

Learn MoreMaterial Price Tracker

Get the latest U.S. retail prices and view historical trends for common building materials.

Track PricesConstruction Newsletter

Delivering construction education directly to your inbox once a month.

Learn MoreProject Management

Stay current on the trends that are helping teams streamline key workflows, from RFIs and submittals to reporting and budget tracking.

Explore Project ManagementPro contributors

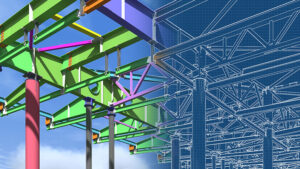

Preconstruction

Learn how to create accurate estimates, win more bids, and leverage technology like BIM to set your projects up for success before work begins.

Explore PreconstructionPro contributors

Role-Based Learning

Get started with sets of construction education courses and project trainings for your role.

50+ Courses

Project Manager

Master project planning & oversight. Learn Procore tools & essential construction education to lead successful projects.

25+ Courses

Field Operations

Boost on-site efficiency and productivity. Get Procore product training and vital construction operation skills.

20+ Courses

Safety

Ensure a safer jobsite. Gain Procore safety expertise and critical construction education for compliance and risk reduction.

Construction Newsletter

Keep Learning

Subscribe to Blueprint, Procore’s free construction newsletter, to get content from industry experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Financial Management

Master the principles of financial management to keep your projects on budget and profitable.

Explore Financial ManagementPro contributors

Risk Management

Protect your projects and people. Explore the latest in health and safety, mental health, insurance, and surety to mitigate risks.

Explore Risk ManagementPro contributors

Made for the construction industry, by the construction industry.

Our articles are crafted with insights from those who know the construction industry best. Business owners, executives, project managers, and industry leaders share their experiences and expertise to provide you with valuable, real-world knowledge.

Scroll Less, Learn More with Blueprint

Sign up for Procore's industry leading newsletter that delivers education directly to your email inbox once a month.